Drought Doesn’t Discriminate

No Water, No Food

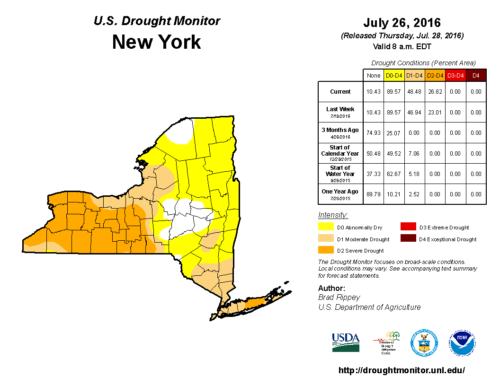

This summer, much of the northeast has suffered from a lack of rainfall. Western New York saw the worst drought since 1943. Farmers have been hit hard. Dairy farmers, because they rely on wide expanses of pasture and often do not have the capacity to irrigate, are forced to purchase food for cattle that can’t forage enough to sustain milk production. Many farmers that do have irrigation use rivers and ponds as their sources of water, and don’t have an alternate option when those water bodies are too low. The CSA farm I worked at for years in Hadley, MA used the Fort River to irrigate. Running pipes was a massive effort saved for dire situations: 25′ sections of 6″ aluminum pipe had to be loaded onto the truck, then each section walked out into the field on our shoulders, attached by hand, and connected to a hydrant. My former boss now runs Winter Moon Farm. The land he currently grows on doesn’t have the buried pipes and river access that we had back then, so in the midst of the drought he shelled out the money to drill a well. Since his whole business plan relies on fall crops that need to be seeded and germinate during the middle of the summer in order to mature before the first frost, spending the money was a make or break move.

Longer Dry Seasons

All this talk of drought in Western Massachusetts felt like deja vu to me. I spent several years in Nicaragua, working in the sustainable agriculture sector, where drought – la sequía – persists and dries up wells and rivers and the cash flows of smallholder farmers. Along the pacific region of the country, the six months of expected rain is essential for farmers to plant and harvest annual crops, and for perennials to live through the six-month dry season. This year was the third year in a row of less than average rainfall during the rainy season. During a recent visit in April, I found cattle and fruit farmers in distress. The Eco-Centro I continue to work with as a board member started a new line of credit specifically for cattle farmers whose wells had dried up. The loans allow them to deepen their wells in the hopes that just a few meters farther would strike the tip of the receding aquifer. The new line of credit was designed to extend deeper than just what the well-diggers pick-axe could achieve. Recipients of the loans were invited to workshops on water conservation, and asked to commit to implementing water-saving methods on their farm, apply mulch to any irrigated land, and sign promises that they would only run their irrigation in the early morning or late evening to reduce evaporation and conserve water.

At Gertrudis and Antonio Solís’s farm, the pasture was dry and brittle. Their garden that I helped them establish four years ago was reduced to less than 1/3 the size to accommodate what they could realistically water. A loan had helped them deepen their well so that it was recharging more often. But Don Antonio needs to set an alarm every three hours during the night to change over the valves on the irrigation system and avoid watering during the day. It’s hard for me to feel like that was a complete success. There is so much more that needs to be done to help farmers who are so dedicated to sustainable, diversified food production, to live the quality of life they deserve.

Supporting Farmers

Over the last six months I have watched farmers in two very different parts of the world, many of whom I have worked alongside, to plan and plant and harvest, struggle similarly under the burden of climate factors out of their control. This is not a kind of solidarity to celebrate. If prices actually rose to cover the costs that these farmers are pulling out of their pockets and from their nights of sleep, maybe consumers would realize the value in spending more of their own time and money voting for policies – and politicians – that support climate change mitigation, investment in renewable energy, and protection of natural resources that provide environmental services like carbon sequestration.

At Regenerative Design Group, we help farmers to develop master plans and implement land-management practices that build resilience to increasingly common climate fluctuations like drought. Establishing silvopasture and fodder hedgerows for grazing animals, using swales to maximize water infiltration, and building the organic matter in soil through regenerative practices are proven methods of increasing a farm’s overall productivity and ability to withstand extreme weather. Bringing these technologies and practices to farmers around the world is one way that we work in solidarity with the stewards of the land and providers of our sustenance, whether they are in the tropics or in our hometowns in the US.

– Rachel Lindsay

Comments (0)