Integrated Urban Farm Design

Cultivating Food, Community, and Clean Water in Cities

Urban farm design is challenging, impactful, and transformative. Challenging because designers, farm managers, and organizations need to navigate complex zoning codes and permitting requirements, tight spaces, contaminated or degraded soils, and high real estate prices. Impactful because of the potential for urban farms to contribute to the health of a city by producing fresh food with minimal transportation costs, sequestering carbon, preserving green space, filtering stormwater, and increasing wildlife habitat. And transformative because it strengthens a movement at the forefront of social change by working to combat food apartheid, racial injustice, and economic oppression.

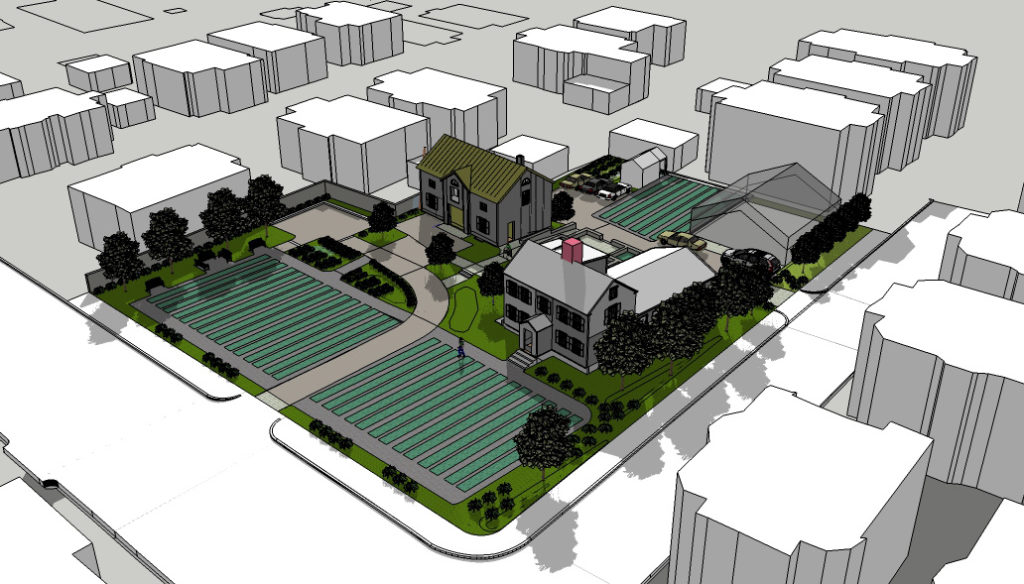

The urban farming movement knows that there are a host of benefits that come with growing food in urban spaces. As designers, we help organizations and farmers understand the full potential of land, defining goals that become farm elements like annual growing space, perennial crops, greenhouses, outdoor classrooms, irrigation systems, and composting systems. Clearly stating the goals of a project will help resolve choices that may need to be made later in the design process, when spaces available for these components might be in conflict.

Our next task is rigorous analysis. Starting at the broad neighborhood scale and working down to each decimal foot of the property, we catalog as much information as we can to understand the full productive, ecological, economic, and social potentials of the site. Finally, we puzzle-piece the desired farm components into place, paying careful attention to drainage, safe vehicular and all-ability pedestrian access, and solar gain.

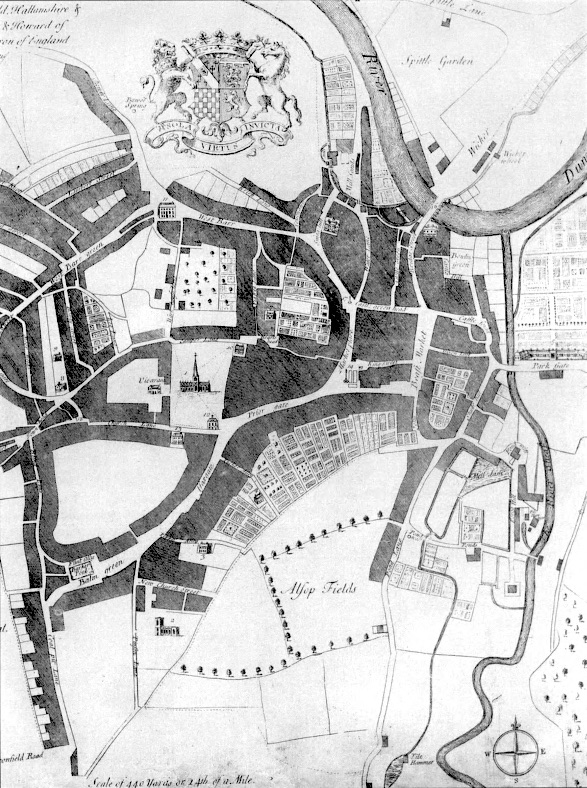

Farming in cities is not a new venture. In fact, since the development of the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia, many cities have grown up on top of prime agricultural land, as people congregated near sources of food and transportation. The global history of urban farming and gardening is closely tied to race and class. In 18th century Europe, allotment gardens on the outskirts of cities were given to lower class citizens as a form of welfare. (National Allotment Society, 2018)

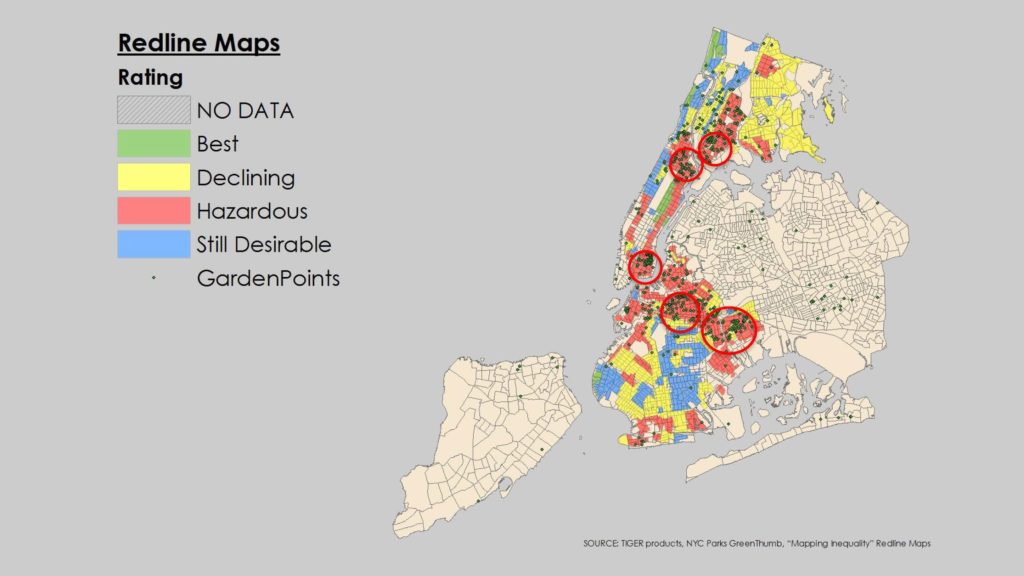

Immigrants to the US from all over the world have used urban plots of land to grow food, not just to supplement low wages but also as a means of cultural expression and sustenance by growing vegetables and fruits from their home cuisines. In times of war and economic depression, the US government campaigned to remove the social stigma of urban gardening, espousing it as a patriotic way for middle-class white families to contribute to war-relief efforts. Today, however, the majority of gardens in New York City still fall within “redlined” districts – neighborhoods historically populated by lower-class European immigrants and black migrants from the south (Arancibia, 2017). The role of urban farms and gardens as spaces for cultural identity and empowerment cannot be dismissed during the design process. Space for education, art, and community organization should be among the components considered for a new urban farm.

Regenerative Design Group is proud to have helped get over a dozen urban farms and gardens up and running. Nuestras Raices in Holyoke, MA, Gardening the Community in Springfield, MA, Grow Food Northampton in Northampton, MA, and the Urban Farming Institute in Boston, MA are some of the organizations we have partnered with to design productive urban spaces. As cities anticipate increased precipitation and higher temperatures due to climate change, focusing resources on productive green spaces is imperative. Integrating ecological functions within the social and historical context of urban agriculture makes projects like the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm in the Mattapan neighborhood of Boston valuable assets for environmental and social justice movements.

– Rachel Lindsay, Associate Landscape Designer

Sources:

National Allotment Society, “A Brief History of Allotments” 2018 https://www.nsalg.org.uk/allotment-info/brief-history-of-allotments/

Penniman, Leah “Uprooting Racism in the Food System,” 2018 http://www.soulfirefarm.org/media/

Comments (0)