Productive Conservation in a Changing Climate

A Destructive Storm

In 2011, Hurricane Irene hit New England, and it hit hard. Four to ten or more inches of rain fell, all within 24 hours. Irene brought New England its most destructive flooding since 1938 and quickly became the 7th costliest hurricane in United States history. Some of that cost was inevitably shouldered by our region’s farmers, who often sit in the lowlands along the fertile tributaries of the Connecticut River. Across Vermont, for example, 476 farms reported damage to 9,100 acres at an estimated cost of $20 million. (UVM) Here in the Pioneer Valley, the Westfield River rose almost 20 feet in a matter of hours, and the Deerfield River rose over 15 feet in the same period. (Bent 2011) Numerous farmers within the floodplain of these rivers lost half their crop, some lost all, while others found their fields under a foot of silt and debris, including large trees. (MassLive 2011)

Fertile and Fragile

The story of Hurricane Irene highlights a dilemma native to the rocky, glacial soils of New England: our most productive farmland is often located in the places most vulnerable to flooding. The river delivers fertility, and uncertainty. This problem is becoming more acute as climate change progresses in New England. According to the National Climate Assessment, annual precipitation has increased by approximately five inches – more than 10% – since 1895. Additionally, “the Northeast has experienced a greater recent increase in extreme precipitation than any other region in the United States; between 1958 and 2010, the Northeast saw more than a 70% increase in the amount of precipitation falling in very heavy events” [Global Change]. Increased precipitation means increased risk to floodplain farms, farmers, local ecosystems, and economies. How can we reconcile this dilemma? How can we design agricultural systems that are as productive as a farm while being as structurally robust and ecologically beneficial as a forest? One method is Productive Conservation.

Integrating Perennials

Productive Conservation is an attempt to balance human needs with the broader ecology, to be profitable for farmers without jeopardizing the integrity of vulnerable soils. Productive Conservation relies on perennial plants for their deep root systems to keep soils in place, trap sediment, absorb excess nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, and improve the vitality of cropland and waterways. Perennial plants also withstand the vicissitudes of annual weather patterns better than their annual counterparts; be it a drought year or a flood year a tree will almost always outperform a carrot, all with much less input of time and energy. With thoughtful selection and placement of perennial plants, we can mimic the layered growth patterns and resilience of a floodplain forest while matching the yield of a diversified orchard or herb farm. Such a landscape is useful for both humans and wildlife, and secures and improves soil fertility for successive generations.

A Model along the Mill River

Along the Mill River in Florence, MA on the Grow Food Northampton Farm site, an exceptional vision for Productive Conservation is already taking shape that will transform a historic field into a model of viable floodplain agriculture. Sitting within the ten-year floodplain, this six-acre field has a 10% chance of at least some flooding every year and is characteristic of many of the vulnerable acres that faced devastation in 2011. In fact, during Hurricane Irene, the Mill River overflowed its banks and a wide, shallow stream rushed south across Meadow Street, uprooting clumps of japanese knotweed and carving a channel through an open farm field before joining the river’s main course in the southern corner of the property.

Below: A succession of aerial photographs helps to illustrate patterns of moisture in the tilled fields during the growing season and make clear which areas are prone to flooding. Annual crops planted along the eastern edge of the property frequently developed poorly, leaving areas of bare soil exposed. In 2011, a cover crop was sown to repair some of the damage cause by the Irene flooding. By 2011 the field had become home to the Grow Food Northampton Community Garden, and cover cropping continues on the eastern field abutting the river.

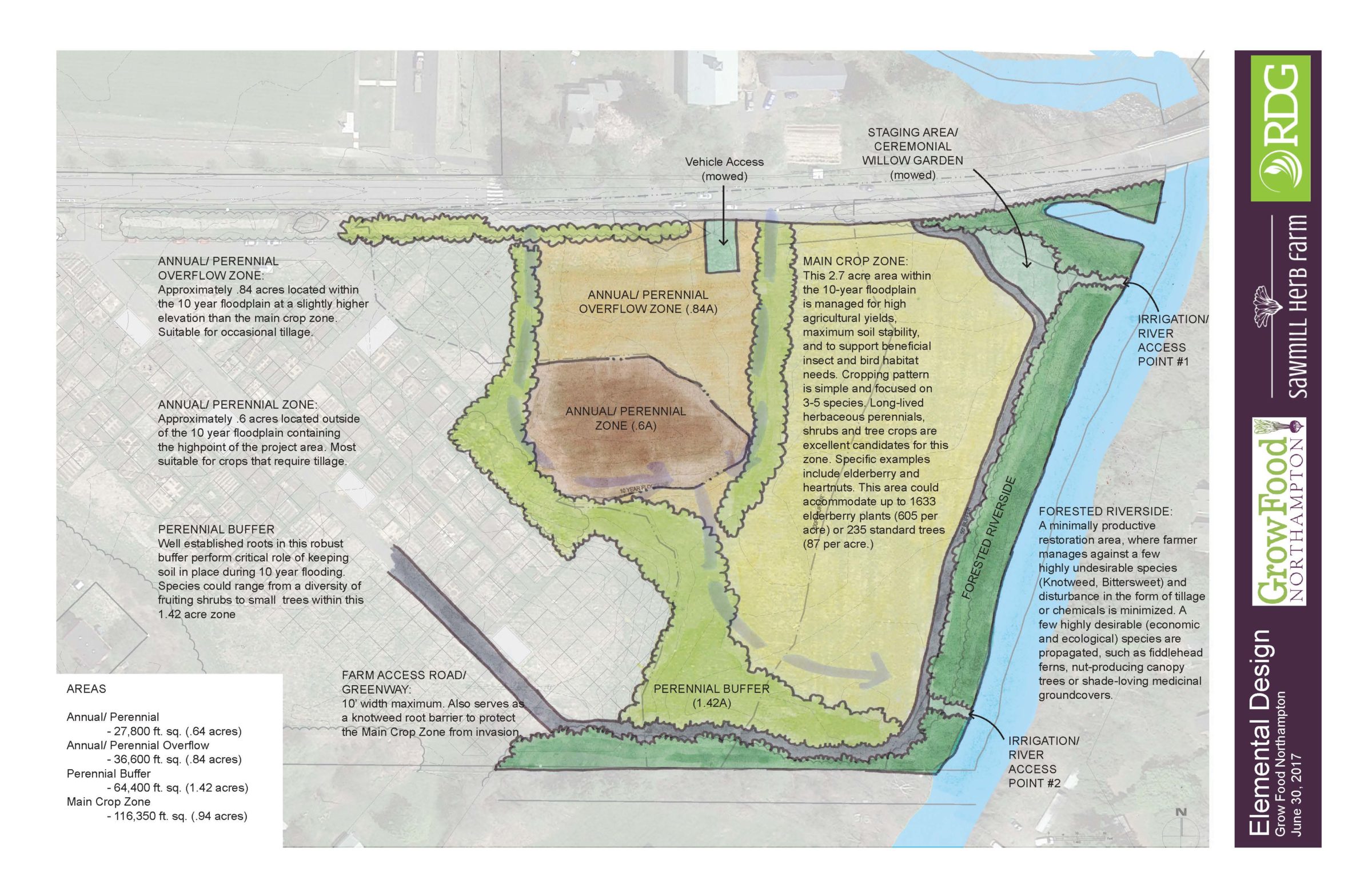

Plans are being conceived (see concept sketches below) by the Regenerative Design Group, Grow Food Northampton, and local farmers to redesign this floodplain field into a resilient landscape that produces food for local markets. Where for hundreds of years there has been annual tillage, these plans suggest a diverse array of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants that will yield nuts, berries, vegetables, medicinal and culinary herbs, and ornamental crops. Suitable species will be of ecological and economic benefit. For example, in New England elderberries are a fast-growing perennial shrub that are valuable for their floral, culinary and medicinal qualities. Heartnut is another likely candidate that produces a tasty, marketable “niche” crop that can eventually be harvested for timber. Hundreds of other species of trees and shrubs perform similar functions while providing perennial native wildlife habitat and sequestering carbon in their woody trunks and branches. Where once there were vulnerable soils demanding seasonal inputs, there will be a vibrant ecology that sustains itself with little input other than the time, labor, and skill of an attentive farmer.

Building Partnerships

The vision for the parcel abutting the Mill River in Florence is a collective one, the fruit of a partnership between farmer, nonprofit advocacy group and designers. Seen from a bird’s eye view, this model holds significant promise for our economy, environment, and society as a whole. With over 250 acres of agricultural land within 200’ of major rivers in the Mill River watershed alone, this project has the potential to impact large numbers of farmers across the Connecticut River Valley. If this site is successful, we will soon have a local model that can serve as a source for inspiration and replication in this region and beyond.

Hurricane Irene was a wake-up call for those concerned about the escalating risks of a changing climate in New England. Yet, we need to remember that a storm of similar size will come again – the only uncertainty is when, and whether or not we will rise to the challenge. If we design our landscapes with this in mind, next time we will be prepared when the river rises.

– Eric DePalo

(For an in depth look at the effects of climate change in the northeast, please refer to Confronting Climate Change in the U.S. Northeast, a document produced by the Northeast Climate Impacts Assessment Synthesis Team.)

For a short video on productive conservation please see.. https://vimeo.com/68650254 (Keith Morris, Willow Crossing Farm, Inhabit Film) For some footage of the flood levels along the Mill River… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mQx2lhYKtYY

Sources: (Bent) High-Water Marks from Tropical Storm Irene for Selected River Reaches in Northwestern Massachusetts, August 2011 By Gardner C. Bent, Laura Medalie, and Martha G. Nielsen https://pubs.usgs.gov/ds/775/ (MassLive 2011) http://www.masslive.com/news/index.ssf/2011/08/hurricane_irene_flooding_devas.html (UVM) http://www.lcbp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/ImpactIreneVermontAgriculture.pdf (Global Change) http://nca2014.globalchange.gov/report/regions/northeast#intro-section-2

Comments (0)